Since 2013, annual emissions of a banned chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) have increased by around 7,000 tons from eastern China, according to new research by an international team of scientists that includes researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego.

The study, “Increase in CFC-11 emissions from eastern China based on atmospheric observations,” will be published May 23 in the journal Nature.

Last year, it was reported that emissions of one of the most important ozone depleting substances, CFC-11, had increased. This surprise finding indicated to researchers and policy makers around the world that someone somewhere was likely producing thousands of tons of CFC-11, despite a global phase-out since 2010 under the Montreal Protocol.

“Through global monitoring networks such as the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Global Monitoring Division (NOAA GMD), scientists have been making measurements of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) in the atmosphere for over 40 years,” said Matt Rigby, a lead author of the study and Reader in Atmospheric Chemistry at the University of Bristol in England. “In recent decades, we’ve primarily seen declining CFC emissions reflected in these measurements because of the Montreal Protocol. Therefore, it was unexpected when we saw that, starting around 2013, global emissions of one of the most important CFCs suddenly began to grow.”

This finding was concerning because CFCs are the main culprits in depletion of the stratospheric ozone layer, which protects us from the sun’s ultra-violet radiation. Any increase in emissions of CFCs will delay the time it takes for the ozone layer, and the Antarctic ozone “hole,” to recover.

But where were these new emissions coming from? Until now, researchers only had an indication that at least part of the source was located somewhere in eastern Asia.

The study “represents an important and particularly policy-relevant milestone in atmospheric scientists’ ability to tell which regions are emitting ozone-depleting substances, greenhouse gases, or other chemicals, and in what quantities,” said Ray Weiss, a geochemist at Scripps and study co-author.

“Initially our monitoring stations were set up in remote locations, far from potential sources. This was because we were interested in collecting air samples that were representative of the background atmosphere, so that we could monitor global changes in concentration,” said Ron Prinn, a co-author of the new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Weiss and Prinn are among leaders of the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), an international monitoring network that provided data for the study.

To pinpoint the sources, measurements are required closer to industrialised regions. In this case, the clue to the location of the new CFC-11 emissions came from two AGAGE stations in eastern Asia.

“Our measurements show ‘spikes’ in pollution, when air arrives from industrialised areas. For CFC-11, we noticed that the magnitude of these spikes increased after 2012, indicating that emissions must have grown from somewhere in the region,” said Sunyoung Park from Kyungpook National University in South Korea, who leads the Gosan measurement station on Jeju Island, to the south of the Korean peninsula. Park, a lead author of the paper is currently on sabbatical at Scripps.

Similar signals had also been noticed at a Japanese National Institute of Environmental Science station on Hateruma island, close to Taiwan.

To establish which countries were responsible for the growing pollution levels at the Korean and Japanese monitoring stations, an international team of modelling groups at University of Bristol, the UK Met Office, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa), and MIT ran sophisticated computer models that determined the origin of air samples measured at Gosan and Hateruma.

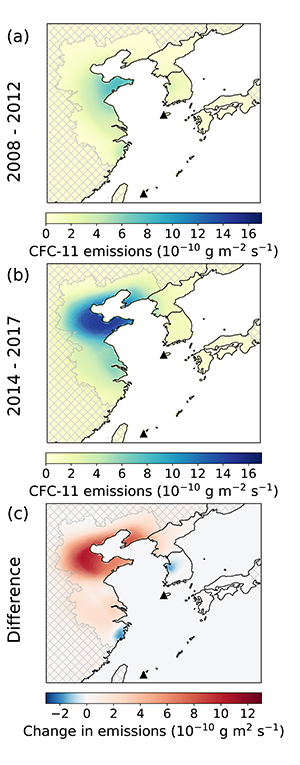

“From the Korean and Japanese data, we used our models to show that emissions of CFC-11 from north eastern China had increased by around 7,000 tons per year after 2013, particularly in or around the provinces of Shandong and Hebei,” said Luke Western, a University of Bristol atmospheric modeler. “We didn’t find evidence of increasing emissions from Japan, the Korean peninsula, or any other country to which our networks are sensitive.”

To investigate the possibility that the new emissions from China could be the result of a release to the atmosphere of CFC-11 that was produced before the ban, the team considered a range of possibilities.

“CFC-11 was used primarily in foam blowing, so we looked at estimates of the amount of CFC-11 that could be locked up in insulating foams in buildings or refrigerators that were made before 2010, but the quantities were far too small to explain the recent rise, Rigby said. “The most likely explanation is that new production has taken place, at least prior to the end of 2017, which is the period covered in our work.”

While the new study has identified a substantial fraction of the global emissions rise, it is possible that smaller increases have also taken place in other countries, or even in other parts of China.

“Our measurements are sensitive only to the north eastern part of China, western Japan and the Korean peninsula and the remainder of the AGAGE network sees parts of North America, Europe and southern Australia,” said Park. “There are large swaths of the world for which we have very little detailed information on the emissions of ozone-depleting substances.”

“It is now vital that we find out which industries are responsible for the new emissions,” Rigby said. “If the emissions are due to the manufacture and use of products such as foams, it is possible that we have only seen part of the total amount of CFC-11 that was produced. The remainder could be locked up in buildings and chillers and will ultimately be released to the atmosphere over the coming decades.”

Previous reports by the Environmental Investigation Agency and the New York Times have suggested that Chinese foam manufacturers were using CFC-11 after the global ban, and Chinese authorities have identified and closed down some illegal production facilities.

While this new study cannot determine which industry or industries are responsible, it provides a clear indication of large increases in emissions of CFC-11 from China in recent years. These increases, likely from new production, account for a substantial fraction of the concurrent global emission rise.