UPDATE: With March rainfall in the books, the San Diego region's precipitation has bumped up to 83.8 percent of its average water-year rainfall. However, the March storms were not as potent in Northern and Central California, and the Sierra Nevada stands at 45 percent and California overall is at 53.4 percent (though they are getting another boost from storms this week). Researchers say this season is emblematic of the boom-or-bust quality of California precipitation that is only expected to become more pronounced as a consequence of climate change. Scripps Oceanography climate scientists are researching aspects of historical variability, which is feeding into downscaled future projections to better anticipate how these extremes may change and possibly amplify in future decades.

Recent rains giving San Diego a late-season soak have brought the tally for all Southern California up to more than 70 percent of its yearly average, but statewide there remains a larger deficit, said climate scientists at Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego.

The flurry is out of the ordinary, said scientists, since most of Southern California’s storminess and accompanying natural water delivery usually occurs between December and February.

The state overall still has received less than half its normal rain and snow amounts with the wet season coming to a close. Despite a stormy week throughout much of California, northern Sierra Nevada precipitation crucial for state water supply is still mired at 42 percent of wet season expectations. Snow water storage is around 50 percent in key watersheds, according to the latest data, including that from the Scripps Oceanography-led California Nevada Applications Program.

Another storm expected next week could help the Sierra water picture improve, but not enough to drive the region out of substantial deficit, said Scripps Oceanography climate scientist Dan Cayan.

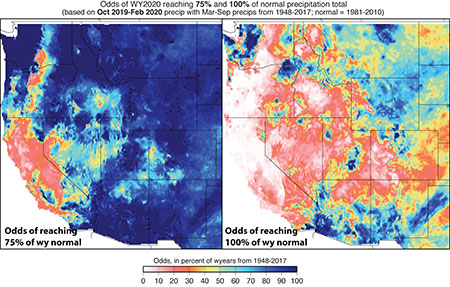

Other calculations based on 72 years of records suggest Northern California has less than a one-in-three chance of reaching even 75 percent of normal this water year, which ends Sept. 30. The estimate does not factor in the wet period over the last week, however, said researchers.

During that week, some locations in the Sierra received a boost to snowpack, including snow depth increasing by over five feet, nearly doubling the snowpack that was there. That increase represented about 20 percent of snow that would fall during an entire winter at that site. Many Sierra sites received 10 percent of the annual average during that same few-day period.

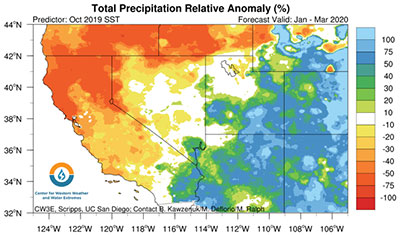

If nothing else, overall, this water year is bearing out predictions made by the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes (CW3E) at Scripps. The forecast was issued last fall for the period from January through March 2020.

“Based on Pacific Ocean surface temperature patterns, we had forecast anomalously dry conditions in the north and central parts of California and wet in the southeast,” said Scripps Oceanography scientist Alexander Gershunov.

Another new forecast tool, which was developed jointly by CW3E and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, was launched by CW3E this winter. It processes outputs from the nation’s leading global weather prediction model run by the National Weather Service. The tool focuses on the West Coast landfall of atmospheric river storms, which are key to California water supply and snowpack. It predicts the odds of atmospheric rivers making landfall at lead times of one to three weeks. The tool presaged the wet period last week, which included a weak atmospheric river.

Additionally, the same weather model currently calls for more rain in Southern California this week and a chance for lighter rainfall next week. Northern California is also predicted to receive more rain and snow in the next 10 days.

– Robert Monroe

This story originally appeared March 19.