Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego is sending ice-dating scientists to Antarctica this fall as part of a friendly international race to uncover the world’s oldest ice.

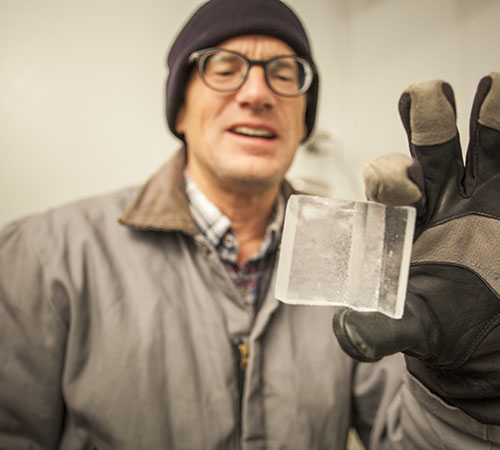

Paleoclimatologist Jeff Severinghaus headed to McMurdo Station, Antarctica this month to test an ice drill that he hopes will help U.S. researchers pinpoint the oldest record of the atmosphere on the planet faster than ever before.

One of the biggest impediments to understanding Earth’s climate history is the lack of samples from the deepest levels of the ice caps. Severinghaus’ lab specializes in dating the age and contents of ancient air preserved in bubbles as the ice sheets froze.

Severinghaus and colleagues at Princeton University published a paper in Nature last month with findings from a study of a two-million-year-old piece of ice. The oldest ice on the planet dates back 2.7 million years ago, a contribution the Severinghaus lab’s ice dating expertise made in a separate 2017 paper.

But these are just “snapshots” in time, Severinghaus said. “That core...was all broken up. It’s like in archaeology when you find pieces of broken pottery you’re trying to put back together,” he said.

The global Antarctic research community is hungry to get their hands on a pristine continuous core, or an unbroken time record, of the entire ice sheet.

The Antarctic ice sheet is almost two miles thick at its deepest point. The conventional way to drill that deep takes about five years, Severinghaus said. That’s the method many other nations, like Japan, Russia and China, are pursuing. But it’s a costly enterprise in terms of labor, travel and instruments.

Plus, nobody really knows where the oldest ice is, Severinghaus said.

“It’s a very big continent. You really need to do reconnaissance,” Severinghaus said. “And reconnaissance has got to be quick and cheap.”

Severinghaus is gambling on a faster way to find it. He is co-leader of a team that developed a radically new approach by building an ice drill that could theoretically condense five years of drilling into just 48 hours.

How does it save time? Conventional drills can only remove one or two meters of core before unloading those sections at the surface. The US-RAID (rapid access ice drill) is faster because it doesn’t take a core. It instead chips away at the ice and continuously flushes those chips to the surface with a non-freezing fluid. While that makes extracting a conventional ice core impossible, it allows for a quick age estimate of the deep ice to pinpoint a location that’s will be worth a five-year investment drilling for the full core.

Severinghaus hatched his plan for the reconnaissance ice drill with John Goodge, a geologist at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. The two met serendipitously at the Antarctic McMurdo Station cafeteria back in 2010.

“I said, well shoot, if you could drill to the bottom of the whole ice sheet, why stop there?” Goodge said. He shared his desires with Severinghaus to extract Antarctic bedrock, which would be another first for the science world.

The National Science Foundation has invested $10.5 million in the drill’s design and development since 2013. The drill the two designed together could nab a 50-meter rock core that would answer questions about Antarctica’s geologic origins.

Severinghaus and Goodge first tested the drill in the mountains of Utah. This December will be the third test of the drill in Antarctica and Severinghaus is hoping for positive results.

The 50-ton drill travelled by ship from Ventura, Calif., to Antarctica in 2015. It now waits for its makers to begin further testing at Minna Bluff near McMurdo Station where a 600-meter thick glacier sits atop bedrock.

The diamond-tipped RAID could eventually be used to extract three-billion-year-old Antarctic bedrock. Ninety-eight percent of the continent is covered in ice. Ice drilling is very expensive so few endeavor to dig into the rock below. Geologists like Goodge typically study already-exposed outcroppings that poke through the Transantarctic Mountains.

Goodge said studying the bedrock could uncover questions about Antarctica’s history like when ice sheets first formed or how the continent was assembled. Some evidence shows Antarctica and North America were once joined together as part of a supercontinent called Rodinia, Goodge said.

Glaciologists and geologists putting their heads together in Antarctica could yield important information about modern climate change. There’s strong evidence that parts of West Antarctica are melting at a very rapid rate, Goodge said.

“The bigger question is what’s happening in East Antarctica because there’s a lot more sea level rise potential if it begins to melt as well,” Goodge said. “So we really need to understand what those conditions are.”

As part of a separate effort to find more ancient shards, Severinghaus sent graduate student Jacob Morgan to work with a team at Princeton University. The team is drilling at Allan Hills, roughly 130 miles from McMurdo, where Morgan will spend eight weeks camping on blue ice — which is very old ice that’s not buried underneath a younger layer of snow. (See map of both locations here).

Researchers suspect ice in this region is old because fallen meteorites that struck Earth millions of years ago were found preserved on its surface.

Up to a certain point in history, scientists have compiled a record from all the information an ice core has to offer.

One mystery that a continuous ice core older than 800,000 years might explain is why there was a sudden change—in geologic time—in the Earth’s climate cycle between small ice sheets and large ice sheets. Scientists refer to these stages as interglacial and glacial.

Between 2.8 million and 1.2 million years ago, it took 41,000 years for the Earth to transition between being warm and cold episodes. But about one million years ago, that transition slowed to every 100,000 years.

In the context of Earth’s 4.5-billion age, a change that occurred just one million years ago is fairly recent, especially to a paleoclimatologist like Severinghaus.

“That’s an unsolved mystery,” Severinghaus said. “But is it telling us something we need to know for the future?”

Morgan, Severinghaus’ student, may also strike it lucky in his Allan Hills expedition and find the oldest ice in a shorter core that takes even less time to drill.

Morgan and Severinghaus will return to Scripps in spring with ancient ice, and hopefully new discoveries, in tow.

More information: https://www.nature.com/news/super-fast-antarctic-drills-ready-to-hunt-for-oldest-ice-1.18649